No matter where else I go or how far my work travels exhibiting in Jamaica always stirs me up, and showing at the current National Biennial in Kingston is no exception. The consensus is that the show is perhaps the best biennial to date and there is a palpable excitement about the exhibition. Much of the work confidently breaks out of the traditional mold of Jamaican art. It is more challenging and ambitious, both in terms of scale and content. But it is also reveals some of the major deficits that exist in the Jamaican art scene.

If the 2010 Biennial saw the rise of photo based work, this year marked the step into new media. Video installations by Storm Sauter, Ebony Patterson, Olivia McGilchrist and Oneika Russel are among the exhibitions highlights. Russel combines animation, filmed and found images to present her highly idiosyncratic but affecting A Natural History 4. Sauter’s Tied, a ten minute short film, poetically interweaves the contradictory internal and external worlds of a woman in an apparently joyful and loving relationship. Patterson’s The Observation (Bush Cockrel) – A fictitious History continues the artist’s investigation of Jamaican male sexuality. Two men dressed in heavily patterned clothing and wearing feathered masks roam around a patch of Jamaican bush. Here the play between artificiality and nature come to the fore and the strutting bush cockles are dandified men exploring a jungle of real and fake flora.

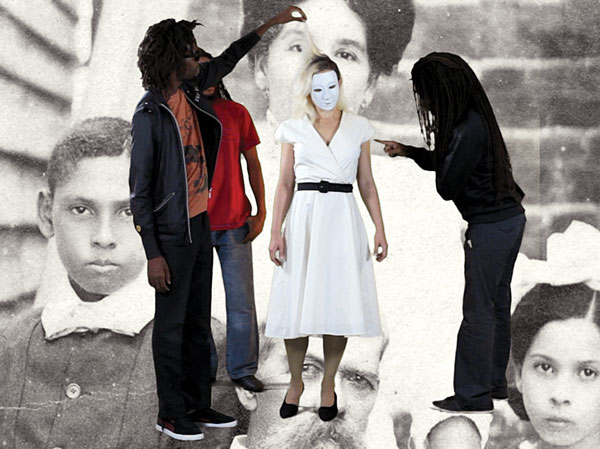

McGilchrist’s Ernestine and Me is a humorous yet poignant exploration of cultural identity. Set against a backdrop of photographs of a Jamaican family of mixed racial heritage McGilchrist portrays herself as ‘Whitey’, a blond haired girl in a white dress with a white plastic mask. Throughout the ten minute video she is variously taunted, tormented and teased by a cast of characters ranging from dreadlocked youth to school-girls to uptown and downtown women. At times playing rag doll, at times playfully engaging with her tormentors McGilchrist is danced spun and has her hair braided, all to an infectious ska/reggae beat. What falls out of the piece are the often unspoken tensions between race and class in Jamaica and the insistence that people conform to a predetermined place in society. It considers what it means to be alien, what constitutes legitimacy and how much of our ancestral baggage we should or choose to carry.

Strong work has also come from some of our other young artists but here the fissures in the current state of Jamaican art start to emerge. Some of the strongest images in the show come from the cameras and digital dark rooms of O’Neil Lawrence, Marlon James, and Marvin Bartley. Lawrence shows one of the pieces from his much acclaimed Son of a Champion series, while James’ Gisele is a disquieting portrait of self-harm.

Bartley’s Birth of Venus is a skillfully and meticulously constructed image based on Botticelli’s original by the same name. However here Bartley chooses to hyper-sexualize his subjects. While his strategy of populating the all white world of classical art history with black bodies is a sound one his representation of the female body in this context remains problematic. Bartley consciously draws from a history that asserted the role of women as objects and while he does perhaps give them a degree of sexual agency here, his women are still essentially props for male desire.

The same problem exists to a much larger degree in the work of Stefan Clarke. It’s difficult to read His Life; Faith/Love/Death as anything other than violent male fantasy complete with axe murderer, lesbian love and women in bondage. Of course the objectification of women is nothing new to Jamaican art. It exists in a supposedly more benign form in the nudes of Barrington Watson and the stylized photographic silhouettes of countless photographers. It’s also touched on by Philip Thomas’ Upper St. Andrew Concubine, a beautifully painted triptych whose central panel is a semi nude woman on a bed, the two side panels showing sides of beef.

Sex, desire and even violence are all legitimate topics for art and I would hate to see Jamaican art sanitized by ‘politically correct’ versions of representation but it’s still distressing that no one even seems to notice cases of blatant objectification.

Visible also in the show is the widening gap between artists willing to take risks and challenge themselves and those more intent on keeping within their established artistic boundaries. Although this is often seen as a division between young and old several of our more established artists have shown themselves willing to push themselves out of their comfort zones to produce mature and powerful work. Hope Brooks’ Slavery Trilogy takes on the notion of racial hierarchies successfully venturing into the type of content heavy work that she scrupulously avoided for much of her career. Judith Salmon’s Memory Pockets is a quiet but effective piece inviting audience participation

Laura Facey’s installation De Hangin Of Phibba An Her Private Parts An De Bone Yard is perhaps her most powerful piece to date. Here Facey has moved away from her symbolist tendencies with a work that deals with material and form in a much more primal way. If other artist in the exhibition showed male fantasies of violence and pointed to racial tension in Jamaica, here is their result, a massive and tortured block of cedar like flayed flesh complete with female genitalia and a floor covered with oversized wooden bones.

Also worthy of mention are the gouache and mixed media drawings A Collection of Strange Fruit by New Jersey bases Shoshanna Weinberger and the starkly arresting painting of a goat’s head by recent Edna Manley College graduate Greg Bailey. Other recent graduates of the College are also pushing themselves as they explore new and non-traditional mediums and challenge themselves with both scale and content. Although some of this work needs to mature there is nevertheless a sense of excitement and promise.

The exhibition lets us see two sides of Omari Sediki Ra’s work. In his exhibition as 2011 Silver Musgrave Medallist we see one of Jamaica’s most potent and political imagists. Here Ra challenges Jamaica’s Eurocentric art audiences with his Black Nationalist vision and cutting social commentary. Ra’s work in the main exhibition however seems to be almost a caricature of itself and lacks the raw impact of the Musgrave exhibition. I was left wondering whether he’s become more interested in mocking the Jamaican art establishment than actually making art. Maybe he has a point.

All round the 2012 Biennial is a powerful and demanding exhibition. Jamaican art is undergoing a period of ambitious expansion with many of our younger artists and several of the more established willing to break new ground. But it is also a world with some serious deficits. Number one among these is the lack of critical engagement with the work. Across the Caribbean one is hard pressed to find anything other than celebratory writing on art and this is much to our detriment. We have to learn to give and accept criticism and learn how to take personality and ego out of the equation. The result would not only be stronger artwork; a healthy dialogue around art would actually allows it to embed itself more deeply in the culture amplifying its power and relevance.

Many of the strongest works in the exhibition cast a critical eye on Jamaican society with the aim of enabling growth and change. It’s time we as artists credited ourselves with the same.