by Toby Lawrence

The vision of R. Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) brought together geometric principles with utopian philosophy to create functional and inhabitable structures that were, in essence, ideological yet demonstrated the capacity of innovation and creativity to prompt social change. These structures, such as his geodesic domes, also represent Fuller’s interest “in technology insofar as it would enhance the quality of life of ordinary people.”[i] In his adoption of Fuller’s spherical constructions, Charles Campbell has found a medium that brings his painting into three-dimensional form[ii] to feature “complex image surfaces, playing between heavily loaded political narratives and utopian ideals.”[iii] A series of free-standing spheres make up a large portion of the works in the Transporter exhibition held in conjunction with Campbell’s production residency at Open Space. Approximately a metre in diameter, each sphere is constructed of triangular shapes cut from brown cardstock with white silkscreened imagery and held together with factory-made bulldog clips. At present, the project also comprises a large-scale triptych painting entitled Bagasse alongside new work that evolved out of the spherical constructions into new and undetermined forms with interactive possibilities. As only one component of the Transporter project, the spheres concretize the intentional visual reference to Fuller’s geodesic domes and clearly represent Campbell’s explorations related to aspirational and utopian futures—which initially led him to consider Fuller’s ideas.[iv]

The allusion to utopianism is made through the connection to Fuller in the form that Campbell has chosen to reproduce again and again At the same time, these works call into question the foundations and context of utopianism through the imagery that adorns his spheres. In Campbell’s view, the imagery is representative of both voluntary and forced human migration, alongside the dichotomy of attraction and repulsion. Looking at the spheres, Campbell aims to create this dichotomous space for the viewer through obfuscated images drawn from the colonial history of his native Jamaica: shackles, vultures, Jamaican Maroon soldiers, slave canoes, and machetes. Imagery such as the empty shackles demonstrate pluralistic signification, as the constraints are open to set free or open to receive, while the vultures demonstrate both the beauty and freedom of flight alongside the repulsion of predatory activity. Further, the canoes used to transport enslaved Africans from the coast of Africa to the slave ships represent, in Campbell’s words, “African-on-African violence, where it would be Africans actually rowing the canoes and Africans in the hold of the canoes, but really it is all human-on-human violence. We are all complicit.”[v] The repeated and rotated white images on the tangible spherical forms, installed seemingly at random throughout the gallery space, employ aesthetic interest and appeal in order to attract. Repulsion is subsequently revealed with greater observation.

The carefully chosen images reference a history that garners little attention in this city, at this point in time, and, in the wake of Idle No More and increased visibility of Indigenous peoples and issues, it has never been more clear that an endured collective amnesia and disinterest has enabled significant holes in the collective Canadian knowledge of the histories that have shaped our present ways of life. Here, Campbell’s Transporter project pushes forward the unrelenting need for greater education regarding the intricacies of historic events—a need for historiography where history is rhizomatic, where the archives of individual histories replace the linear and hierarchical histories of specified places.

Returning to Campbell’s reference to Fuller, I am compelled to consider the implications of utopianism and their relationship to history. I will begin with an idea put forward by German historian Jörn Rüsen: “History wishes to establish ‘how it actually was’; utopia is interested in showing how it actually should or could be.”[vi] Contrary to first thought, this view is not defined as dichotomous; rather, it takes into account the “interrelationship between both modes of looking” through which our daily human lives are interpreted.[vii] More, regardless of its designation as reality, history shares its characterization with utopia as constructed through social and political systems, which are class specific and, therefore, ideological.[viii] Considering Fuller’s utopian desire to create “anticipatory comprehensive design solutions that would benefit the largest segment of humanity while consuming the fewest resources,”[ix] such vision falls in opposition to the impetus of slavery and the imagery that dominates Campbell’s exhibition. The sustained consequences of Christopher Columbus’s fifteenth-century historically sanctioned desire to “[discover] a vast territory of abundant material possibilities.”[x] (in other words, to search for a fantastical and unrealizable utopia) are manifest through systemic injustices. Writing for Infinite Islands: Contemporary Caribbean Art, organized by the Brooklyn Museum, curator Tumelo Mosaka explains,

Having found very little gold and material wealth, Columbus and his men transformed the [Caribbean] islands into industrial production sites for raw materials in the service of the West. This new industrial economy required a large dependable labour force to work the plantations, since the arrival of the Europeans had caused a massive depopulation of the indigenous Indians, who resisted colonialism and were exterminated as a result of massacres, famine, and foreign disease such as smallpox. The colonizers therefore imported a workforce of slaves from Africa and, later, indentured servants from India. The plantations became central to the Western economy, generating raw products such as sugar, coffee, leather, indigo, cocoa, and cotton for European consumption.[xi]

Campbell’s conflicting conflation of Fuller’s utopian structure with the oppressive imagery of shackles, slave canoes, and machetes provides a critical space in which to consider the impetus and the consequence of slavery. Further, the social and geographic origins of an individual or collective utopian vision must be made visible—thus to consider its specific relationship to history—as one shaped by subjectivity and sociopolitical context . While Fuller aspired to mobilize the creative potential of individuals, the notions and implications of universal accessibility and inclusivity are conversely subject to specific social and geo- graphic ideology. Again, what constitutes universality in the classification of humanity may be uniquely determined by political affiliation. The vision of the “new world”—a utopia of new potential, freedom, and plenty—made place for the subordination of slaves that fuelled the sugar trade represented in Bagasse and was abhorrently justified through historically positioned discursive and ideological processes that enabled a hierarchical system of establishing degrees of humanity.[xii]

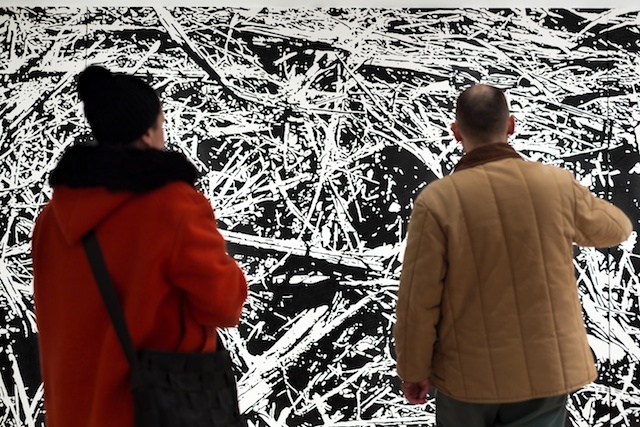

Of Bagasse, the large painting spanning the east wall of Open Space and depicting the remnants of sugarcane cultivation discarded after the extraction of juices, Campbell explains, “On the level of narrative, Bagasse references the proto-capitalist economy of the sugar plantation and acts as metaphor for economic systems that view society and human relationships as by-products.”[xiii] Such ideas formed the starting point for the Transporter project, and, considering the immediate size and the fragmentation of the painting’s content, the project further “exploit[s] the difference between the optical and cognitive understanding of an image.”[xiv] Here, again, sociopolitical context comes to play, also highlighting the hierarchical systems found within the history of art.

The allusion to modernist painting in Bagasse via its scale and abstracted painterly application also functions to subvert the controlled materiality of ideology and hierarchy through, in essence, an interlacing cause and effect scenario. As Jamaica did not obtain full independence until 1962, the events of modernism are therefore inseparable from colonial rule and, further, inseparable from forced migration and agricultural production for foreign economic gain. Bagasse, in turn, perforates the modernist veil with the inclusion of content, and where it can no longer sustain itself through surficial treatment—as mere paint on canvas—the events of Jamaica’s history are made visible, exposing a multiplicity of investigative possibilities stemming from the enlarged depiction of the sugarcane by-product, bagasse, and the suggestion of race relations in the usage of black and white paint. Likewise, the imagery and form of the spheres flip the investigative possibilities outward. In this rupture, the realities and particularities of Jamaican history are brought to the surface of a modern utopian form. With the potential for ruin found in the impending removal of just one bulldog clip, the modernist constructs fastened by these mass-produced and imported commercial products no longer exist without the consideration of the assorted histories that have contributed to their present state.

Returning to the silkscreened imagery that adorns Campbell’s spheres, the determined references not only implicate the instability of history and the notion of utopia but take into account the subjectivity of the human body. The body is present both in absentia and as actual figures. The inclusion of empty shackles offers another example of multiplicity, evoking both freedom and loss: the bodies of those who perished in transit and the bodies of those who gained freedom through the abolition of slavery or further migration. Such corporeal signification once again compels me to consider the manner in which degrees of humanity are shaped by systemic events and ideologies, creating and reinforcing what is and is not considered a human body in a given social and geographic context, and the subsequent justification of the capture, enslavement, and forced migration of people from Africa, alongside other locations such as India, to the Caribbean. Transporter brings history into view, and as with Campbell’s alter ego, Actor Boy (2009– present), it is utopian thinking, the creative acts of imagining alternate realities, that enables the possibility of change and therefore, the collective imagination joined by corporeal presence becomes a functional agent of change, of revolution.

New work made during Campbell’s residency at Open Space relinquishes the utopian reference through a shift away from the spherical form, yet the centrality of history and politics is retained through the repeated triangular segments with replicating imagery. Keeping the geometric system of interlocking triangles, the new work initially expanded to create experimental shapes that encased structures found within the gallery, such as chairs and columns. In a way, Campbell returns to the traditional form of painting with Portal by creating a diagonal grid of criss-crossed cord, prominently framed by two-by-six-inch planks and mounted on the gallery’s north wall. This new structure acknowledges its function within the institution of art. It evokes the notion of containment within the white cube, and speaks to the limitations of the gallery space to disseminate ideas and innovations beyond its participating audience. The snaking geometric forms appear imbued with the desire to escape the frame, to escape the confines of the gallery space; and as such, they bridge Campbell’s interest in the potential messiness and awkward accidental encounters that can occur when similar works are taken out of the gallery context and into the street for unexpected viewers, as Campbell intends to do.[xv]

Transporter ultimately facilitates space for potential futures, chance encounters, and interconnecting histories. It demonstrates our multiplicities of historical (and continuing) experiences as Canadians, as inhabitants of a nation of First Peoples, of immigrants, and of settlers, whose livelihoods and present realities are forever as they are through colonization. Our histories are far from the glories of proverbial victories shaped by potential utopias. They are real. They are raw. And they are often untold and forgotten.

Transporter ultimately facilitates space for potential futures, chance encounters, and interconnecting histories. It demonstrates our multiplicities of historical (and continuing) experiences as Canadians, as inhabitants of a nation of First Peoples, of immigrants, and of settlers, whose livelihoods and present realities are forever as they are through colonization. Our histories are far from the glories of proverbial victories shaped by potential utopias. They are real. They are raw. And they are often untold and forgotten.

Toby Lawrence is a curator and writer from Victoria, British Columbia, who has been actively involved in creative endeavours throughout her life She is currently the Downtown Gallery Coordinator at Nanaimo Art Gallery.

[i] Howard P Segal, “America’s Last Genuine Utopian?” New Views on R. Buckminster Fuller edited by Hsiao-Yun Chu and Roberto G Trujillo (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 38–39

[ii] Charles Campbell in conversation with author, January 31, 2013

[iii] Charles Campbell Art, “Transporter,” accessed February 6, 2013, http://charlescampbellart com/artwork/projects/transporter

[iv] Author in conversation with Charles Campbell, January 31, 2013

[v] Charles Campbell, artist talk at Open Space Arts Society, Victoria, BC, March 1, 2013

[vi] Jörn Rüsen, “Introduction: History and Utopia,” in Historien 7 (2007): 6 The quote comes from Leopold von Ranke, Geschichten der romanischen und germanischen Völker von 1494–1514, Sämtliche Werke, vol 33, Leipzig: Duncker und Humblot, 1855, p viii

[vii] Ibid

[viii] Fredric Jameson, “The Politics of Utopia,” in New Left Review 25 (January/February 2004): 46–47

[ix] K Michael Hays and Danna Miller, “Introduction,” in Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe edited by K Michael Hays and Dana Miller (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2008), iix

[x] Tumela Mosaka, Infinite Islands: Contemporary Caribbean Art (New York: Brooklyn Museum in association with Philip Wilson Publishers, 2007), 15

[xi] Ibid, 16

[xii] For further discussion, see: Nelson Maldonado-Torres, “On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of Thought ” Cultural Studies 21, no 2–3 (March/May 2007): 240–270

[xiii] Charles Campbell Art

[xiv] Charles Campbell, “Transformation Set,” Small Axe 17 (March 2005): 82

[xv] Campbell in conversation with author, February 22, 2013